Rethinking Multilingualism in the Digital Age: From Babel to Balance

With over 8,000 languages spoken around the world, you’d expect the internet to be a rich tapestry of global voices. However, in reality, fewer than 120 languages have meaningful representation online. This isn’t just a technical issue but a deep-rooted problem of inclusion. In the digital age, language has become one of the most overlooked dimensions of the digital divide.

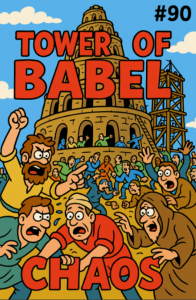

Lessons from the Tower of Babel at IGF2025

At the 2025 Internet Governance Forum (IGF) in Lillestrøm, a session titled ‘Tower of Babel Chaos’ offered an eye-opening look at what happens when English is no longer the default. Organised by Diplo and the Civil Society Alliances for Digital Empowerment (CADE), the session flipped the script: English was set aside, and participants were encouraged to speak in their native (first) languages, which included Afrikaans, Arabic, Bengali, Bulgarian, Chinchewa, Dutch, English, French, German, Italian, Maltese, Mandarin, Norwegian, Polish, Samoan, Serbian, Sinhala, Spanish, and Swahili.

The result? A mix of confusion, creativity, and insight. Some attendees found themselves forming impromptu language groups. Others discovered they were the only speakers of their language in the room. For many, it was a rare opportunity to experience firsthand the communication challenges non-English speakers face daily in global spaces. Some came away seeing English as a practical necessity; others viewed it as a barrier that excludes.

Multilingualism is more than a communication choice – It’s about inclusion

UNESCO has long warned that when languages disappear from the digital space, it’s not just words that are lost but entire cultures. As Dr Tawfik Jelassi put it at the WSIS+20 High-Level Event in Geneva, the internet today is like a ‘vast library where most languages have no books on the shelves.’

The statistics paint a stark picture: 85% of web content exists in the top ten languages, mostly English. Meanwhile, Africa – home to a third of the world’s languages, sees less than 0.1% of its websites in African local languages. The result? Entire communities are left out of the online conversation, unable to participate fully or share their stories on their own terms, in their own words.

AI: Promise and pitfalls

AI offers new tools to help close the language gap, but it’s not a silver bullet. As Ken Huang from the Singapore IGF pointed out in the Tower of Babel Session, AI can technically support any language. In reality, though, it only works well with about 100. The rest are limited by a lack of data, low investment, or technical constraints.

There are reasons to be hopeful. OpenAI’s collaboration with Iceland to support the Icelandic language using GPT-4 is one example of how AI can help preserve and promote minority languages. But we also have to be realistic. AI still tends to favour English and other dominant languages and struggles with nuance, idiom, and oral traditions.

Participants in the IGF session made another key point: AI doesn’t think in language – it processes mathematical structures. This could make it a neutral communication tool, but only if it’s built with fairness and cultural awareness in mind.

Beyond English: Exploring middle grounds

The IGF experiment made it clear that it’s not just a choice between English-only and complete chaos. There’s a middle path: cross-linguistic communication. In some cases, speakers of different languages were able to understand each other thanks to shared vocabulary, similar roots, or common loanwords – like Portuñol (a Portuguese-Spanish blend), Spanglish, or English-Hindi hybrids.

On the technical side, progress is being made, too. Internationalized Domain Names (IDNs), for instance, are helping expand internet access to users of non-Latin scripts like Arabic, Chinese, and Cyrillic. ICANN’s push for Universal Acceptance is another important step – ensuring that email addresses and URLs can be written in any language. But awareness and adoption still lag behind.

The role of policy and community

Tools alone won’t fix linguistic exclusion. What’s needed is a mix of policy support, community leadership, and political will. UNESCO’s 2003 Recommendation on Multilingualism and the ongoing UN Decade of Indigenous Languages have spurred some governments to act. ICANN’s domain name support programme is another step in the right direction.

As highlighted during WSIS+20, the most successful efforts are the ones led by the communities themselves. Projects in Latvia and among Sámi speakers in northern Europe show how language digitisation can thrive when native speakers take the lead. In Africa, initiatives like the African Storybook Project are proving that locally driven content creation in local languages is not only possible, it’s essential.

From chaos to coexistence

The main takeaway from all these discussions? Multilingualism doesn’t have to be messy. English will likely remain a useful tool in international diplomacy and business. But it shouldn’t be the only tool. There’s room for many languages – and many ways of communicating – to coexist online.

Language isn’t just a technical matter. It’s about identity, culture, representation, and fairness. As UNESCO’s Guilherme Canela de Souza noted, multilingualism is not merely a desirable feature, it is a digital right. It’s how we make sure everyone has a voice in shaping the digital world.

Refining the chaos: Toward a truly global internet

We’re at a turning point. With advances in AI, new policy frameworks, and growing awareness of linguistic inequality, the global community has both the tools and the responsibility to build an internet where every language can thrive.

Moving from the chaos of Babel to a balanced, inclusive digital ecosystem won’t be easy, but it’s more than possible: It’s necessary. It starts with recognising that, rather than a barrier, language is a bridge, if we choose to build it that way.

Author’s Note: This blog synthesises insights from the IGF 2025 ‘Tower of Babel Chaos‘ session, UNESCO and ICANN initiatives, and the broader conversation on AI and multilingualism. The future of digital inclusion depends on our ability to see language not as a barrier, but as the foundation of a truly global internet. If we want a digital world that’s truly global, we need to start treating every language like it matters – because it does.

The CADE project and this publication were co-funded by the EU. Its contents are the sole responsibility of CADE and do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.