Future of work

The Internet changed how we work. ICTs have blurred the traditional routine of work, leisure, and sleep (8+8+8 hours), especially within corporations, businesses with increasing international exposure and on online platforms. It is increasingly difficult to distinguish where work begins and where it ends. These changes in working patterns may require new labour legislation, addressing issues such as working hours, the protection of workers’ interests, training, and remuneration. While this phenomenon requires broader elaboration, the following aspects are of direct relevance to Internet governance:

- The Internet created the environment for a high level of temporary workers, short-term workers, and independent contractors. The term ‘permatemp’ was coined to describe workers who work for a business on a long-term basis on regularly renewed short-term contracts. This results in lower levels of social protections of the workforce.

- The debate on whether platform workers should be classified as independent contractors or employees, and the related labour rights implications.

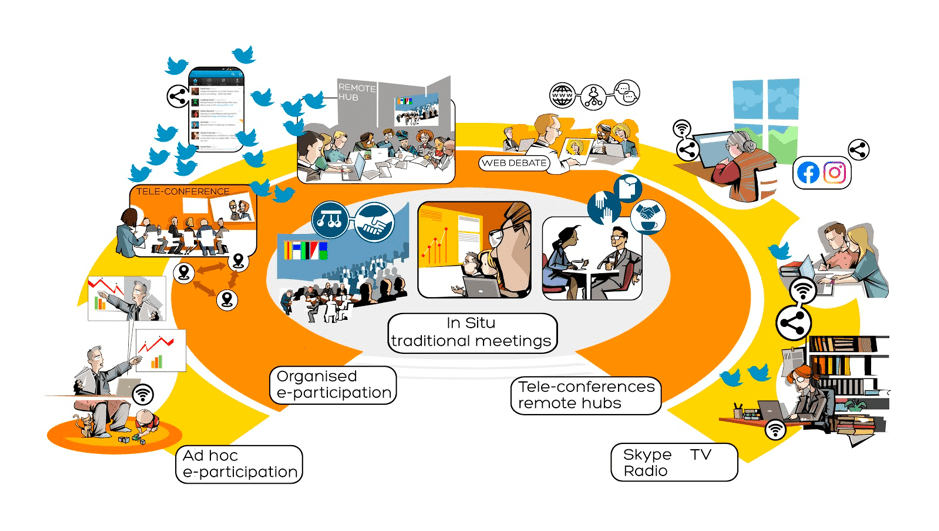

- Teleworking has become increasingly relevant with the continued development of telecommunications, especially in regard to broadband access to the Internet.

- Outsourcing ICT service sector work to other countries, such as call centres and data processing units, is on the rise. A considerable number of these activities have already been transferred to low-cost countries, mainly in Asia and Latin America.

- Many adults lack the right skills for emerging jobs.

Privacy in the workplace

In the field of labour law, one important issue is the question of privacy in the workplace. Is an employer allowed to monitor employee use of the Internet such as the content of e-mail messages or access to certain websites? Jurisprudence is gradually developing in this field, with a variety of new solutions now available.

In France, Portugal, and Great Britain, some legal guidelines and a few cases have restricted the surveillance of employee emails. The employer must provide prior notice of any monitoring activities. In Denmark, courts considered a case involving an employee’s dismissal for sending private emails and accessing a sexually-explicit chat website. The court ruled that dismissal was not lawful since the employer did not have an Internet use policy in place prohibiting non-work related use of the Internet. Another rationale applied by the Danish court was the fact that the employee’s use of the Internet did not affect their working performance. In 2017, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that employers are allowed to monitor their employees’ emails only if they are notified in advance. Monitoring policies should also be accompanied by adequate and sufficient safeguards against abuse. In the US, employers have the legal right to monitor employee emails if there is a legitimate business purpose for doing so.

An additional point of concern arising with the ever-growing use of social networking is the blurring of boundaries between private and working life. Employee behaviour and commentary on social networking sites may address various topics, from the workplace and co-workers to employer strategies and products, deemed as personal (and private) opinions, but which may considerably affect the image and reputation of companies and colleagues. These cases shall serve as sufficient ground for summary dismissal.

The impact of AI on the future of work

The emergence of online sharing economy platforms has been one of the major transformations of work over the last decade. Sharing economies operate in different sectors, including transportation, delivery, IT, translation, editing, among many others. They generate new sources of income and work opportunities in developed countries, but also in regions where local economies are stagnant. Online sharing economy platforms allow workers to work from any place and at any time.

Most commonly, workers on sharing economy platforms are classified independent contractors. Regulators worldwide are concerned whether they receive adequate compensation and social protection. The employment status of such workers has been disputed in many jurisdictions, including in the UK, the US, and Belgium.

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) has addressed the following risks and opportunities for sharing economy platform workers:

- Inadequate remuneration as a consequence of high competition and permeability of the platforms;

- Unsustainable working hours, considering the low remuneration and the lack of regulation of the income of independent contractors; and

- Lack of representation due to the decentralisation and isolation of the workforce.

Labour law

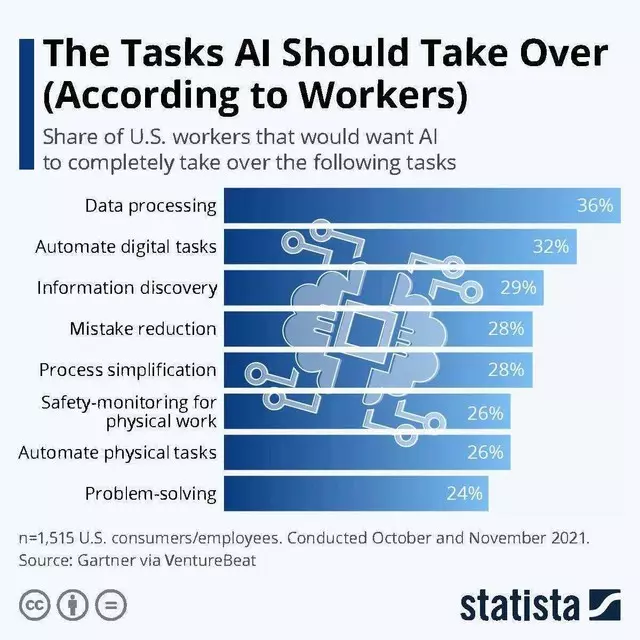

Artificial intelIigence (AI) will change working practices in the global economy. While AI represents a powerful force for economic growth and the creation of new employment opportunities, it will displace many existing jobs by automating several tasks. Automation will vary substantially by sector. In the near future, some of the sectors that are likely to be most affected by AI are the financial and transportation sectors. Alternatively, sectors such as healthcare, education, and creative industries are expected to be less affected due to a greater reliance on social skills and human interaction.

Given that AI increasingly requires high-skilled employees, governments and businesses are focused on creating special training to prepare their workers for the coming decades. Governments are also investing in new initiatives to address unemployment rates due to the implementation of AI in several industries. So far, several EU nations have established a holistic, human-centric, and user-centred approach as AI is implemented at workplaces. In Germany, the key priority is the implementation of the ‘National Further Training Strategy’ focused on creating continuous digital training for workers. In addition, a ‘House of the Self-Employed’ is to be established to support one-person companies and freelancers in the digital employment market. The House will provide information on the right to set up unions, as well as strategies that could be used to improve the rights of freelancers and for those working for online platforms. In France, the Grand École du Numérique was launched to support digital skills training for people at risk of unemployment. The Future National Strategy in Belgium aims at developing open online courses on AI to train at least 1% of Belgian citizens. Canada, Denmark, Lithuania, the Czech Republic, and Portugal have also set national guidelines for developing skills and training employees for a future of work with AI. In China, professionals and scientists are targeted to receive formal education on AI. Finland is planning to enhance unemployment security as an increasing number of jobs will be replaced by AI. South Korea prepares to reform and strengthen the social support system in order to ensure that all citizens will be able to enjoy the benefits of the intelligent information society.

Labour law has traditionally been a national issue. However, globalisation and the Internet have led to the internationalisation of labour issues. With an increasing number of individuals working for foreign entities and interacting with colleagues globally, there is now an increasing need for stronger labour regulations on an international scale. This aspect was recognised in the WSIS declaration, which, in paragraph 47 calls for the respect of all relevant international norms in the field of the ICT labour market.

Multilateral organisations have also been engaged in reflecting on regulatory solutions for the labour market.

In 2017, the ILO established a commission focused on developing a human-centric agenda for future of work policies. Among the key aspects assessed by the commission are new forms of work, the changing nature of work, the need for lifelong training for employees, commitment to foster greater inclusivity and gender equality, and the essential role of universal social protection.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has provided a set of policy guidelines related to new forms of work, including platform workers. Key ideas include the reduction of incentives for the misclassification of workers, better working conditions, adequate social protection coverage, and opportunities for collective bargaining.

In 2017, the G7 Future of Work Forum was launched by G7 labour and employment ministers as a platform to share strategies, good practices, and experiences of G7 countries in addressing emerging labour market challenges, such as ageing in times of rapid digitalisation, social inequality, and unemployment in the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

In 2018, the European Commission issued guidelines for Member States to address structural weaknesses in education and training systems in the context of technological change. Member States shall promote productivity and employability by nurturing relevant skills and competencies that respond to current and future labour market needs.